Search terms and the flu: preferring complex models

Simplicity has its draws. A simple model of some phenomena can be quick to understand and test. But with the resources we have today for theory building and prediction, it is worth recognizing that many phenomena of interest (e.g., in social sciences, epidemiology) are very, very complex. Using a more complex model can help. It’s great to try many simple models along the way — as scaffolding — but if you have a large enough N in an observational study, a larger model will likely be an improvement.

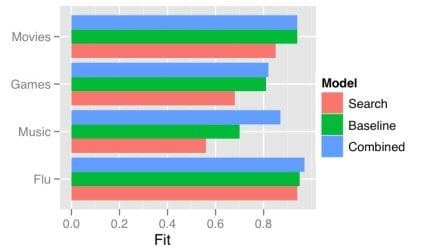

One obvious way a model gets more complex is by adding predictors. There has recently been a good deal of attention on using the frequency of search terms to predict important goings-on — like flu trends. Sharad Goel et al. (blog post, paper) temper the excitement a bit by demonstrating that simple models using other, existing public data sets outperform the search data. In some cases (music popularity, in particular), adding the search data to the model improves predictions: the more complex combined model can “explain” some of the variance not handled by the more basic non-search-data models.

This echos one big takeaway from the Netflix Prize competition: committees win. The top competitors were all large teams formed from smaller teams and their models were tuned combinations of several models. That is, the strategy is, take a bunch of complex models and combine them.

One way of doing this is just taking a weighted average of the predictions of several simpler models. This works quite well when your measure of the value of your model is root mean squared error (RMSE), since RMSE is convex.

While often the larger model “explains” more of the variance, what “explains” means here is just that the R-squared is larger: less of the variance is error. More complex models can be difficult to understand, just like the phenomena they model. We will continue to need better tools to understand, visualize, and evaluate our models as their complexity increases. I think the committee metaphor will be an interesting and practical one to apply in the many cases where the best we can do is use a weighted average of several simpler, pretty good models.

Multitasking among tasks that share a goal: action identification theory

Right from the start of today’s Media Multitasking Workshop1, it’s clear that one big issue is just what people are talking about when they talk about multitasking. In this post, I want to highlight the relationship between defining different kinds of multitasking and people’s representations of the hierarchical structure of action.

It is helpful to start with a contrast between two kinds of cases.

Distributing attention towards a single goal

In the first, there is a single task or goal that involves dividing one’s attention, with the targets of attention somehow related, but of course somewhat independent. Patricia Greenfield used Pac-Man as an example: each of the ghosts must be attended to (in addition to Pac-Man himself), and each is moving independently, but each is related to the same larger goal.

Distributing attention among different goals

In the second kind of case, there are two completely unrelated tasks that divide attention, as in playing a game (e.g., solitaire) while also attending to a speech (e.g., in person, on TV). Anthony Wagner noted that in Greenfield’s listing of the benefits and costs of media multitasking, most of the listed benefits applied to the former case, while the costs she listed applied to the later. So keeping these different senses of multitasking straight is important.

Complications

But the conclusion should not be to think that this is a clear and stable distinction that slices multitasking phenomena in just the right way. Consider one ways of putting this distinction: the primary and secondary task can either be directed at the same goal or directed at different goals (or tasks). Let’s dig into this a bit more.2

Byron Reeves pointed out that sometimes “the IMing is about the game.” So we could distinguish whether the goal of the IMing is the same as the goal of the in-game task(s). But this making this kind of distinction requires identity conditions for goals or tasks that enable this distinction. As Ulrich Mayr commented, goals can be at many different levels, so in order to use goal identity as the criterion, one has to select a level in the hierarchy of goals.

Action identities and multitasking

We can think about this hierarchy of goals as the network of identities for an action that are connected with the “by” relation: one does one thing by doing (several) other things. If these goals are the goals of the person as they represent them, then this is the established approach taken by action identification theory (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987) — and this could be valuable lens for thinking about this. Action identification theory claims that people can report an action identity for what they are doing, and that this identity is the “prepotent identity”. This prepotent identity is generally the highest level identity under which the action is maintainable. This means that the prepotent identity is at least somewhat problematic if used to make this distinction between these two types of multitasking because then the distinction would be dependent on, e.g., how automatic or functionally transparent the behaviors involved are.

For example, if I am driving a car and everything is going well, I may represent the action as “seeing my friend Dave”. I may also represent my simultaneous, coordinating phone call with Dave under this same identity. But if driving becomes more difficult, then my prepotent identity will decrease in level in order to maintain the action. Then these two tasks would not share the prepotent action identity.

Prepotent action identities (i.e. the goal of the behavior as represented by the person in the moment) do not work to make this distinction for all uses. But I think that it actually does help makes some good distinctions about the experience of multitasking, especially if we examine change in action identities over time.

To return to case of media multitasking, consider the headline ticker on 24-hour news television. The headline ticker can be more or less related to what the talking heads are going on about. This could be evaluated as a semantic, topical relationship. But considered as a relationship of goals — and thus action identities — we can see that perhaps sometimes the goals coincide even when the content is quite different. For example, my goal may simply to be “get the latest news”, and I may be able to actually maintain this action — consuming both the headline ticker and the talking heads’ statements — under this high level identity. This is an importantly different case then if I don’t actually maintain the action at the level, but instead must descend to — and switch between — two (or more) lower level identities that are associated the two streams of content.

References

Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1987). What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review, 94(1), 3-15.

- The full name is the “Seminar on the impacts of media multitasking on children’s learning and development”. [↩]

- As I was writing this, the topic re-emerged in the workshop discussion. I made some comments, but I think I may not have made myself clear to everyone. Hopefully this post is a bit of an improvement. [↩]

Social and cultural costs of media multitasking

Today I’m attending the Media Multitasking workshop at Stanford. I’m going to just blog as I go, so these posts are going to perhaps be a bit rougher than usual.1

The workshop began with a short keynote from Patricia Greenfield, a psychology professor at UCLA, about the costs and benefits of media multitasking. Greenfield’s presentation struck me as representing as an essentially conservative and even alarmist perspective on media multitasking.

Exemplifying this perspective was Greenfield’s claim that media multitasking (by children) is disrupting family rituals and privileging peer interaction over interaction with family. Greenfield mixed in some examples of how having a personal mobile phone allows teens to interact with peers without their parents being in the loop (e.g., aware of who their children’s interaction partners are). These examples don’t strike me as particularly central to understanding media multitasking; instead, they highlight the pervasive alarmism about new media and remind me of how “helicopter parents'” extreme control of their children’s physical co-presence with others is also a change from “how things used to be”.

Face-to-face vs. mediated

The relationship of these worries about mobile phones and the allegedly decreasing control that parents have over their children’s social interaction to media multitasking is that mediated communication is being privileged over face-to-face interaction. Greenfield proposed that face-to-face interaction suffers from media use and media multi-tasking, and that this is worrisome because we have evolved for face-to-face interaction. She commented that face-to-face interaction enables empathy; there is an implicit contrast here with mediated interaction, but I’m not sure it is so obvious that mediated communication doesn’t enable empathy — including empathizing with targets that one would otherwise not encounter face-to-face and experiencing a persistent shared perspective with close, but distant, others (e.g., parents and college student children).

Family reunion

Greenfield cited a study of 30 homes in which children and a non-working parent only greeted the other parent returning home from work about one third of the time (Ochs et al., 2006), arguing — as I understood it — that this is symptomatic of a deprioritization of face-to-face interaction.

As another participant pointed out, this could also — if not in these particular cases, then likely in others — be a case of not feeling apart during the working day: that is, we can ask, are the children and non-working parents communicating with the parent during the workday? In fact, Ochs et al. (2006, pp. 403-4) presents an example of such a reunion (between husband and wife in this case) in which the participants have been in contact by mobile phone, and the conversation picks up where it left off (with the addition of some new information available by being present in the home).

Next

I’m looking forward to the rest of the workshop. I think one clear theme of the workshop is going to be differing emphasis on costs and benefits of media multitasking of different types. I expect Greenfield’s “doom and gloom” will continue to be contrasted with other perspectives — some of which already came up.

References

Ochs, E., Graesch, A. P., Mittmann, A., Bradbury, T., & Repetti, R. (2006). Video ethnography and ethnoarchaeological tracking. The Work and Family Handbook: Multi-Disciplinary Perspective, Methods, and Approaches, 387–409.

- Which also means I’m multitasking, in some senses, through the whole conference. [↩]

Motivations for tagging: organization and communication motives on Facebook

Increasing valuable annotation behaviors was a practical end of a good deal of work at Yahoo! Research Berkeley. ZoneTag is a mobile application and service that suggests tags when users choose to upload a photo (to Flickr) based on their past tags, the relevant tags of others, and events and places nearby. Through social influence and removing barriers, these suggestions influence users to expand and consistently use their tagging vocabulary (Ahern et al. 2006).

Context-aware suggestion techniques such as those used in ZoneTag can increase tagging, but what about users’ motivations for considering tagging in the first place? And how can these motivations for annotation be considered in designing services that involve annotation? In this post, I consider existing work on motivations for tagging, and I use tagging on Facebook as an example of how multiple motivations can combine to increase desired annotation behaviors.

Using photo-elicitation interviews with ZoneTag users who tag, Ames & Naaman (2007) present a two factor taxonomy of motivations for tagging. First, they categorize tagging motivations by function: is the motivating function of the tagging organizational or communicative? Organizational functions include supporting search, presenting photos by event, etc., while communicative functions include when tags provide information about the photos, their content, or are otherwise part of a communication (e.g., telling a joke). Second, they categorize tagging motivations by intended audience (or sociality): are the tags intended for my future self, people known to me (friends, family, coworkers, online contacts), or the general public?

On Flickr the function dimension generally maps onto the distinction between functionality that enables and is prior to arriving at the given photo or photos (organization) and functionality applicable once one is viewing a photo (communication). For example, I can find a photo (by me or someone else) by searching for a person’s name, and then use other tags applied to that photo to jog my memory of what event the photo was taken at.

Some Flickr users subscribe to RSS feeds for public photos tagged with their name, making for a communication function of tagging — particularly tagging of people in media — that is prior to “arriving” at a specific media object. These are generally techie power users, but this can matter for others. Some less techie participants in our studies reported noticing that their friends did this — so they became aware of tagging those friends’ names as a communicative act that would result in the friends finding the tagged photos.

This kind of function of tagging people is executed more generally — and for more than just techie power users — by Facebook. In tagging of photos, videos, and blog posts, tagging a person notifies them they have been tagged, and can add that they have been tagged to their friends’ News Feeds. This function has received a lot of attention from a privacy perspective (and it should). But I think it hints at the promise of making annotation behavior fulfill more of these functions simultaneously. When specifying content can also be used to specify recipients, annotation becomes an important trigger for communication.

—————

See some interesting comments (from Twitter) about tagging on Facebook:

- noticing people tagging to gain eyeballs

- exhorting others not to tag bad photos (and thanks)

- collapsing time by tagging photos from long ago

- tagging by parents

(Also see Facebook’s growing use and testing of autotagging [1, 2].)

References

Ames, M., & Naaman, M. (2007). Why we tag: motivations for annotation in mobile and online media. In Proceedings of CHI 2007 (pp. 971-980). San Jose, California, USA: ACM.

Ahern, S., Davis, M., Eckles, D., King, S., Naaman, M., Nair, R., et al. (2006). Zonetag: Designing context-aware mobile media capture to increase participation. Pervasive Image Capture and Sharing: New Social Practices and Implications for Technology Workshop. In Adjunct Proc. Ubicomp 2006.

Activity streams, personalization, and beliefs about our social neighborhood

Every person who logs into Facebook is met with the same interface but with personalized content. This interface is News Feed, which lists “news stories” generated by users’ Facebook friend. These news stories include the breaking news that Andrew was just tagged in a photo, that Neema declared he is a fan of a particular corporation, that Ellen joined a group expressing support for a charity, and that Alan says, “currently enjoying an iced coffee… anyone want to see a movie tonight?”

News Feed is an example of a particular design pattern that has recently become quite common – the activity stream. An activity stream aggregates actions of a set of individuals – such as a person’s egocentric social network – and displays the recent and/or interesting ones.

I’ve previously analysed, in a more fine-grained analysis of a particular (and now changed) interface element for setting one’s Facebook status message, how activity streams bias our beliefs about the frequency of others’ participation on social network services (SNSs). It works like this:

- We use availability to mind as a heuristic for estimating probability and frequency (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973). So if it is easier to think of a possibility, we judge it to be more likely or frequent. This heuristic is often helpful, but it also leads to bias due to, e.g., recent experience, search strategy (compare thinking of words starting with ‘r’ versus words with ‘r’ as the third letter).

- Activity streams show a recent subset of the activity available (think for now of a simple activity stream, like that on one’s Twitter home page).

- Activity streams show activity that is more likely to be interesting and is more likely to have comments on it.

Through the availability heuristic (and other mechanisms) this leads to one to estimate that (1) people in one’s egocentric network are generating activity on Facebook more frequently than they actually are and (2) stories with particular characteristics (e.g., comments on them) are more (or less) common in one’s egocentric network than they actually are.

Personalized cultivation

When thinking about this in the larger picture, one can see this as a kind of cultivation effect of algorithmic selection processes in interpersonal media. According to cultivation theory (see Williams, 2006, for an application to MMORGs), our long-term exposure to media makes leads us to see the real world through the lens of the media world; this exposure gradually results in beliefs about the world based on the systematic distortions of the media world (Gerbner et al., 1980). For example, heavy television viewing predicts giving more “television world” answers to questions — overestimating the frequency of men working in law enforcement and the probability of experiencing violent acts. A critical difference here is that with activity streams, similar cultivation can occur with regard to our local social and cultural neighborhood.

Aims of personalization

Automated personalization has traditionally focused on optimizing for relevance – keep users looking, get them clicking for more information, and make them participate related to this relevant content. But the considerations here highlight another goal of personalization: personalization for strategic influence on attitudes that matter for participation. These goals can be in tension. For example, should the system present…

The most interesting and relevant photos to a user?

Showing photographs from a user’s network that have many views and comments may result in showing photos that are very interesting to the user. However, seeing these photos can lead to inaccurate beliefs about how common different kinds of photos are (for example, overestimating the frequency of high-quality, artistic photos and underestimating the frequency of “poor-quality” cameraphone photos). This can discourage participation through perceptions of the norms for the network or the community.

On the other hand, seeing photos with so many comments or views may lead to overestimating how many comments one is likely to get on one’s own photo; this can result in disappointment following participation.

Activity from a user’s closest friends?

Assume that activity from close friends is more likely to be relevant and interesting. It might even be more likely to prompt participation, particularly in the form of comments and replies. But it can also bias judgments of likely audience: all those people I don’t know so well are harder to bring to mind as is, but if they don’t appear much in the activity stream for my network, I’m less likely to consider them when creating my content. This could lead to greater self-disclosure, bad privacy experiences, poor identity management, and eventual reduction in participation.

References

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “Mainstreaming” of America: Violence Profile No. 11. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10-29.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207-232.

Williams, D. (2006). Virtual Cultivation: Online Worlds, Offline Perceptions. Journal of Communication, 56, 69-87.