Transformed social interaction and actively mediated communication

Transformed social interaction (TSI) is modification, filtering, and synthesis of representations of face-to-face communication behavior, identity cues, and sensing in a collaborative virtual environment (CVE): TSI flexibly and strategically decouples representation from behavior. In this post, I want to extend this notion of TSI, as presented in Bailenson et al. (2005), in two general ways. We have begun calling the larger category actively mediated communication.1

First, I want to consider a larger category of strategic mediation in which no communication behavior is changed or added between different existing participants. This includes applying influence strategies to the feedback to the communicator as in coaching (e.g., Kass 2007) and modification of the communicator’s identity as presented to himself (i.e. the transformations of the Proteus effect). This extension entails a kind of unification of TSI with persuasive technology for computer-mediated communication (CMC; Fogg 2002, Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa 2008).

Second, I want to consider a larger category of media in which the same general ideas of TSI can be manifest, albeit in quite different ways. As described by Bailenson et al. (2005), TSI is (at least in exemplars) limited to transformations of representations of the kind of non-verbal behavior, sensing, and identity cues that appear in face-to-face communication, and thus in CVEs. I consider examples from other forms of communication, including active mediation of the content, verbal or non-verbal, of a communication.

Feedback and influence strategies: TSI and persuasive technology

TSI is exemplified by direct transformation that is continuous and dynamic, rather than, e.g., static anonymization or pseudonymization. These transformations are complex means to strategic ends, and they function through a “two-step” programmatic-psychological process. For example, a non-verbal behavior is changed (modified, filtered, replaced), and then the resulting representation affects the end through a psychological process in other participants. Similar ends can be achieved by similar means in the second (psychological) step, without the same kind of direct programmatic change of the represented behavior.

In particular, consider coaching of non-verbal behavior in a CVE, a case already considered as an example of TSI (Bailenson et al. 2005, pp. 434-6), if not a particularly central one. In one case, auxiliary information is used to help someone interact more successfully:

In those interactions, we render the interactants’ names over their heads on floating billboards for the experimenter to read. In this manner the experimenter can refer to people by name more easily. There are many other ways to use these floating billboards to assist interactants, for example, reminders about the interactant’s preferences or personality (e.g., “doesn’t respond well to prolonged mutual gaze”). (Bailenson et al. 2005, pp. 435-436)

While this method can bring about change in non-verbal behaviors as represented in the CVE and thus achieve the same strategic goals by the same means in the second (psychological) step, it does not do so in the characteristic TSI way: it doesn’t decouple the representation from the behavior; instead it changes the behavior itself in the desired way. I think our understanding of the core of TSI is improved by excluding this kind of active mediation (even that presented by Bailenson et al.) and considering it instead a proper part of the superset – actively mediated communication. With this broadened scope we can take advantage of the wider range of strategies, taxonomies, and examples available from the study of persuasive technology.

TSI ideas outside CVEs

TSI is established as applying to CVEs. Standard TSI examples take place in CVEs and the feasibility of TSI is discussed with regard to CVEs. This focus is also manifest in the fact that it is behaviors, identity cues, and sensing that are normally available that are the starting point for transformation. Some of the more radical transformations of sensing and identity are nonetheless explained with reference to real-world manifestation: for example, helpers walk like ghosts amongst those you are persuading, reporting back on what they learn.

But I think this latter focus is just an artifact of the fact that, in a CVE, all the strategic transformations have to be manifest as representations of face-to-face encounters. As evidence for the anticipation of the generalization of TSI ideas beyond CVEs, we see that Bailenson et al. (2005, p. 428) introduce TSI with examples from the kind of outright blocking of any representation of particular non-verbal behaviors in telephone calls. Of course, this is not the kind of dynamic transformation characteristic of TSI, but this highlights how TSI ideas make sense outside of CVEs as well. To make it more clear what I mean by this, I present three examples: transformation of a shared drawing, coaching and augmentation in face-to-face conversation, and aggregation and synthesis in an SNS-based event application, like Facebook Events.

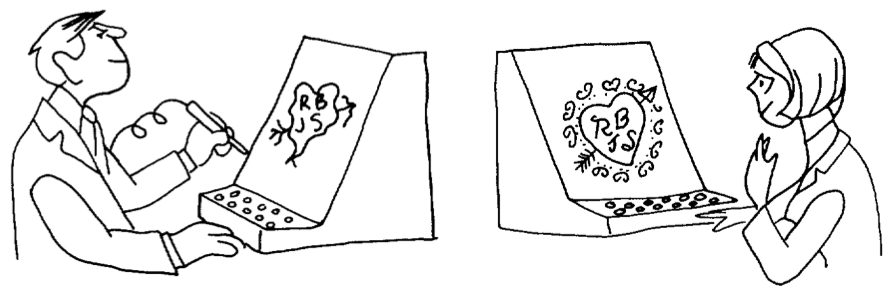

This more general notion of actively mediated communication is present in the literature as early as 1968 with the work of Licklider & Taylor (1968). In one interesting example, which is also a great example of 1960s gender roles, a man is draws an arrow-pierced heart with his initials and the initials of a romantic interest or partner, but when this heart is shared with her (perhaps in real time as he draws it), it is rendered as a beautiful heart with little resemblance to his original, poor sketch. The figure illustrating the example is captioned, “A communication system should make a positive contribution to the discovery and arousal of interests” (Licklider & Taylor 1968, p. 26). This example clearly exemplifies the idea of TSI – decoupling the original behavior from its representation in a strategic way that requires an intelligent process (or human-in-the-loop) making the transformation responsive to the specific circumstances and goals.

Licklider & Taylor also consider examples in which computers take an active role in a face-to-face presentation by adding a shared, persuasive simulation (cf. Fogg 2002 on computers in the functional role of interactive media such as games and simulations). But a clearer example, that also bears more resemblance to characteristic TSI examples, is conversation and interaction coaching via a wireless headset that can determine how much each participant is speaking, for how long, and how often they interrupt each other (Kass 2007). One could even imagine a case with greater similarity to the TSI example considered in the previous case: a device whispers in your ear the known preferences of the person you are talking to face-to-face (e.g., that he doesn’t respond well to prolonged mutual gaze).

Finally, I want to share an example that is a bit farther afield from TSI exemplars, but highlights how ubiquitous this general category is becoming. Facebook includes a social event planning application with which users can create and comment on events, state their plans to attend, and share personal media and information before and after it occurs. Facebook presents relevant information about one’s network in a single “News Feed”. Event related items can appear in this feed, and they feature active mediation: a user can see an item stating that “Jeff, Angela, Rich, and 6 other friends are attending X. It is at 9pm tonight” – but none of these people or the event creator, ever wrote this text. It has been generated strategically: it is encouraging considering coming to the event and it is designed to maximize the user’s sense of relevance of their News Feed. The original content, peripheral behavior, and form of their communications have been aggregated and synthesized into a new communication that better suits the situation than the original.

Source orientation in actively mediated communication

Bailenson et al. (2005) considers the consequences of TSI for trust in CVEs and how possible TSI detection is. I’ve suggested that we can see TSI-like phenomena, both actual and possible, outside of CVEs and outside of a narrow version of TSI in which directly changing (programmatically) the represented behavior without changing the actual behavior is required. Many of the same consequences for trust may apply.

But even when the active mediation is to some degree explicit – participants are aware that some active mediation is going on, though perhaps not exactly what – interesting questions about source orientation still apply. There is substantial evidence that people orient to the proximal rather than distal source in use of computers and other media (Sundar & Nass 2000, Nass & Moon 2000), but this work has been limited to relatively simple situations, rather than the complex multi-sourced, actively mediated communications under discussion. I think we should expect that proximality will not consistently predict degree of source orientation (impact of source characteristics) in these circumstances: the most proximal source may be a dumb terminal/pipe (cf. the poor evidence for proximal source orientation in the case of televisions, Reeves & Nass 1996), or the most proximal source may be an avatar, the second most proximal might be a cyranoid/ractor or a computer process, while the more distant is the person whose visual likeness is similar to that of the avatar; and in these cases one would expect the source orientation to not be the most proximal, but to be the sources that are more phenomenologically present and more available to mind.

This seems like a promising direction for research to me. Most generally, it is part of the study of source orientation in more complex configurations – with multiple devices, multiple sources, and multiple brands and identities. Consider a basic three condition experiment in which participants interact with another person and are either told (1) nothing about any active mediation, (2) there is a computer actively mediating the communications of the other person, (3) there is a human (or perhaps multiple humans) actively mediating the communications of the other person. I am not sure this is the best design, but I think it hints in the direction of the following questions:

- When and how do people apply familiar social cognition strategies (e.g., folk psychology of propositional attitudes) to understanding, explaining, and predicting the behavior of a collection of people (e.g., multiple cyranoids, or workers in a task completion market like Amazon Mechanical Turk)?

- What differences are there in social responses, source orientation, and trust between active mediation that is (ostensibly) carried out by (1) a single human, (2) multiple humans each doing very small pieces, (3) a computer?

References

Eckles, D., Ballagas, R., Takayama, L. (unpublished manuscript). The Design Space of Computer-Mediated Communication: Dimensional Analysis and Actively Mediated Communication.

Fogg, B.J. (2002). Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Morgan Kaufmann.

Kass, A. (2007). Transforming the Mobile Phone into a Personal Performance Coach. Mobile Persuasion: 20 Perspectives on the Future of Influence, ed. B.J. Fogg & D. Eckles, Stanford Captology Media.

Licklider, J.C.R., & Taylor, R.W. (1968). The Computer as a Communication Device. Science and Technology, April 1968. Page numbers from version reprinted at http://gatekeeper.dec.com/pub/DEC/SRC/research-reports/abstracts/src-rr-061.html.

Nass, C., and Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and Mindlessness: Social Responses to Computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81-103.

Oinas-Kukkonen, H., & Harjumaa, M. (2008). A Systematic Framework for Designing and Evaluating Persuasive Systems. In Proceedings of Persuasive Technology: Third International Conference, Springer, pp. 164-176.

Sundar, S. S., & Nass, C. (2000). Source Orientation in Human-Computer Interaction Programmer, Networker, or Independent Social Actor? Communication Research, 27(6).

- This idea is expanded upon in Eckles, Ballagas, and Takayama (ms.), to be presented at the workshop on Socially Mediating Technologies at CHI 2009. This working paper will be available online soon. [↩]

Unconscious processing, self-knowledge, and explanation

This post revisits some thoughts I’ve shared an earlier version of here. In articles over the past few years, John Bargh and his colleagues claim that cognitive psychology has operated with a narrow definition of unconscious processing that has led investigators to describe it as “dumb” and “limited”. Bargh prefers a definition of unconscious processing more popular in social psychology – a definition that allows him to claim a much broader, more pervasive, and “smarter” role for unconscious processing in our everyday lives. In particular, I summarize the two definitions used in Bargh’s argument (Bargh & Morsella 2008, p. 1) as the following:

Unconscious processingcog is the processing of stimuli of which one is unaware.

Unconscious processingsoc is processing of which one is unaware, whether or not one is aware of the stimuli.

A helpful characterization of unconscious processingsoc is the question: “To what extent are people aware of and able to report on the true causes of their behavior?” (Nisbett & Wilson 1977). We can read this project as addressing first-person authority about causal trees that link external events to observable behavior.

What does it mean for the processing of a stimulus to be below conscious awareness? In particular, we can wonder, what is that one is aware of when one is aware of a mental process of one’s own? While determining whether unconscious processingcog is going on requires specifying a stimulus to which the question is relative, unconscious processingsoc requires specifying a process to which the question is relative. There may well be troubles with specifying the stimulus, but there seem to be bigger questions about specifying the process.

There are many interesting and complex ways to identify a process for consideration or study. Perhaps the simplest kind of variation to consider is just differences of detail. First, consider the difference between knowing some general law about mental processing and knowing that one has in fact engaging in processing meeting the conditions of application for the law.

Second, consider the difference between knowing that one is processing some stimulus and that a various long list of things have a causal role (cf. the generic observation that causal chains are hard to come by, but causal trees are all around us) and knowing the specific causal role each has and the truth of various counterfactuals for situations in which those causes were absent.

Third, consider the difference between knowing that some kind of processing is going on that will accomplish an end (something like knowing the normative functional or teleological specification of the process, cf. Millikan 1990 on rule-following and biology) and the details of the implementation of that process in the brain (do you know the threshold for firing on that neuron?). We can observe that an extensionally identical process can always be considered under different descriptions; and any process that one is aware of can be decomposed into a description of extensionally identical sub-processes, of which one is unaware.

A bit trickier are variations in descriptions of processes that do not have law-like relationships between each other. For example, there are good arguments for why folk psychological descriptions of processes (e.g. I saw that A, so I believed that B, and, because I desired that C, I told him that D) are not reducible to descriptions of processes in physical or biological terms about the person.1

We are still left with the question: What does it mean to be unaware of the imminent consequences of processing a stimulus?

References

Anscombe, G. (1969). Intention. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 73-79.

Davidson, D. (1963). Actions, Reasons, and Causes. Journal of Philosophy, 60(23), 685-700.

Millikan, R. G. (1990). Truth Rules, Hoverflies, and the Kripke-Wittgenstein Paradox. Philosophical Review, 99(3), 323-53.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review, 84(3), 231-259.

Putnam, H. (1975). The Meaning of ‘Meaning’. In K. Gunderson (Ed.), Language, Mind and Knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- There are likely more examples of this than commonly thought, but the one I am thinking of is the most famous: the weak supervenience of mental (intentional) states on physical states without there being psychophysical laws linking the two (Davidson 1963, Anscombe 1969, Putnam 1975). [↩]

Source orientation and persuasion in multi-device and multi-context interactions

At the Social Media Workshop, Katarina Segerståhl presented her on-going work on what she has termed extended information services or distributed user experiences — human-computer interactions that span multiple and heterogeneous devices (Segerståhl & Oinas-Kukkonen 2007). As a central example, she studies a persuasive technology service for planning, logging, reviewing, and motivating exercise: these parts of the experience are distributed across the user’s PC, mobile phone, and heart rate monitor.

In one interesting observation, Segerståhl notes that the specific user interfaces on one device can be helpful mental images even when a different device is in use: participants reported picturing their workout plan as it appeared on their laptop and using it to guide their actions during their workout, during which the obvious, physically present interface with the service was the heart rate monitor, not the earlier planning visualization. Her second focus is how to make these user experiences coherent, with clear practical applications in usability and user experience design (e.g., how can designers make the interfaces both appropriately consistent and differentiated?).

In this post, I want to connect this very interesting and relevant work with some other research at the historical and theoretical center of persuasive technology: source orientation in human-computer interaction. First, I’ll relate source orientation to the history and intellectual context of persuasive technology. Then I’ll consider how multi-device and multi-context interactions complicate source orientation.

Source orientation, social responses, and persuasive technology

As an incoming Ph.D. student at Stanford University, B.J. Fogg already had the goal of improving generalizable knowledge about how interactive technologies can change attitudes and behaviors by design. His previous graduate studies in rhetoric and literary criticism had given him understanding of one family of academic approaches to persuasion. And in running a newspaper and consulting on many document design (Schriver 1997) projects, the challenges and opportunities of designing for persuasion were to him clearly both practical and intellectually exciting.

The ongoing research of Profs. Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves attracted Fogg to Stanford to investigate just this. Nass and Reeves were studying people’s mindless social responses to information and communication technologies. Cliff Nass’s research program — called Computers as (or are) Social Actors (CASA) — was obviously relevant: if people treat computers socially, this “opens the door for computers to apply […] social influence” to change attitudes and behaviors (Fogg 2002, p. 90). While clearly working within this program, Fogg focused on showing behavioral evidence of these responses (e.g., Fogg & Nass 1997): both because of the reliability of these measures and the standing of behavior change as a goal of practitioners.

Source orientation is central to the CASA research program — and the larger program Nass shared with Reeves. Underlying people’s mindless social responses to communication technologies is the fact that they often orient towards a proximal source rather than a distal one — even when under reflective consideration this does not make sense: people treat the box in front of them (a computer) as the source of information, rather than a (spatially and temporally) distant programmer or content creator. That is, their source orientation may not match the most relevant common cause of the the information. This means that features of the proximal source unduly influence e.g. the credibility of information presented or the effectiveness of attempts at behavior change.

For example, people will reciprocate with a particular computer if it is helpful, but not the same model running the same program right next to it (Fogg & Nass 1997, Moon 2000). Rather than orienting to the more distal program (or programmer), they orient to the box.1

Multiple devices, Internet services, and unstable context

These source orientation effects have been repeatedly demonstrated by controlled laboratory experiments (for reviews, see Nass & Moon 2000, Sundar & Nass 2000), but this research has largely focused on interactions that do not involve multiple devices, Internet services, or use in changing contexts. How is source orientation different in human-computer interactions that have these features?

This question is of increasing practical importance because these interactions now make up a large part of our interactions with computers. If we want to describe, predict, and design for how people use computers everyday — checking their Facebook feed on their laptop and mobile phone, installing Google Desktop Search and dialing into Google 411, or taking photos with their Nokia phone and uploading them to Nokia’s Ovi Share — then we should test, extend, and/or modify our understanding of source orientation. So this topic matters for major corporations and their closely guarded brands.

So why should we expect that multiple devices, Internet services, and changing contexts of use will matter so much for source orientation? After having explained the theory and evidence above, this may already be somewhat clear, so I offer some suggestive questions.

- If much of the experience (e.g. brand, visual style, on-screen agent) is consistent across these changes, how much will the effects of characteristics of the proximal source — the devices and contexts — be reduced?

- What happens when the proximal device could be mindfully treated as a source (e.g., it makes its own contribution to the interaction), but so does a distance source (e.g., a server)? This could be especially interesting with different branding combination between the two (e.g., the device and service are both from Apple, or the device is from HTC and service is from Google).

- What if the visual style or manifestation of the distal source varies substantially with the device used, perhaps taking on a style consistent with the device? This can already happen with SMS-based services, mobile Java applications, and voice agents that help you access distant media and services.

References

- This actually is subject to a good deal of cross-cultural variation. Similar experiments with Japanese — rather than American — participants show reciprocity to groups of computers, rather than just individuals (Katagiri et al.) [↩]

Update your Facebook status: social comparison and the availability heuristic

[Update: This post uses an older Facebook UI as an example. Also see more recent posts on activity streams and the availability heuristic.]

Over at Captology Notebook, the blog of the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab, Enrique Allen considers features of Facebook that influence users to update their status. Among other things, he highlights how Facebook lowers barriers to updating by giving users a clear sense of something they can right (“What are you doing right now?”).

I’d like to add another part of the interface for consideration: the box in the left box of the home page that shows your current status update with the most recent updates of your friends.

This visual association of my status and the most recent status updates of my friends seems to do at least a couple things:

Influencing the frequency of updates. In this example, my status was updated a few days ago. On the other hand, the status updates from my friends were each updated under an hour ago. This juxtaposes my stale status with the fresh updates of my peers. This can prompt comparison between their frequency of updates and mine, encouraging me to update.

The choice of the most recent updates by my Facebook friends amplifies this effect. Through automatic application of the availability heuristic, this can make me overestimate how recently my friends have updated their status (and thus the frequency of status updates). For example, the Facebook friend who updated their status three minutes ago might have not updated to three weeks prior. Or many of my Facebook friends may not frequently update their status messages, but I only see (and thus have most available to mind) the most recent. This is social influence through enabling and encouraging biased social comparison with — in a sense — an imagined group of peers modeled on those with the most recent performances of the target behavior (i.e., updating status).

Influencing the content of updates. In his original post, Enrique mentions how Facebook ensures that users have the ability to update their status by giving them a question that they can answer. Similarly, this box also gives users examples from their peers to draw on.

Of course, this can all run up against trouble. If I have few Facebook friends, none of them update their status much, or those who do update their status are not well liked by me, this comparison may fail to achieve increased updates.

Consider this interface in comparison to one that either

- showed recent status updates by your closest Facebook friends, or

- showed recent status updates and the associated average period for updates of your Facebook friends that most frequently update their status.

[Update: While the screenshot above is from the “new version” of Facebook, since I captured it they have apparently removed other people’s updates from this box on the home page, as Sasha pointed out in the comments. I’m not sure why they would do this, but here are couple ideas:

- make lower items in this sidebar (right column) more visable on the home page — including the ad there

- emphasize the filter buttons at the top of the news feed (left column) as the means to seeing status updates.

Given the analysis in the original post, we can consider whether this change is worth it: does this decrease status updates? I wonder if Facebook did a A-B test of this: my money would be on this significantly reducing status updates from the home page, especially from users with friends who do update their status.]

Naming this blog “ready-to-hand”: Heidegger, Husserl, folk psychology, and HCI

The name of this blog, Ready-to-hand, is a translation of Heidegger’s term zuhanden, though interpreting Heidegger’s philosophy is not specifically a major interest of mine nor a focus here. Much has been made of the significance of phenomenology, most often Heidegger, for human-computer interaction (HCI) and interaction design (e.g., Winograd & Flores 1985, Dourish 2001). And I am generally pretty sympathetic to phenomenology as one inspiration for HCI research. I want to just note a bit about the term zuhanden and my choice of it in a larger context — of phenomenology, HCI, and a current research interest of mine: cues for assuming the intentional stance toward systems (more on this below).

The Lifeworld and ready-to-hand

Heidegger was a student of Edmund Husserl, and Heidegger’s Being and Time was to be dedicated to Husserl.1 There is really no question of the huge influence of Husserl on Heidegger.

My major introduction to both Husserl and Heidegger was from Prof. Dagfinn Føllesdal. Føllesdal (1979) details the relationship between their philosophies. He argues for the value of seeing much of Heidegger’s philosophy “as a translation of Husserl’s”:

The key to this puzzle, and also, I think, the key to understanding what goes on in Heidegger’s philosophy, is that Heidegger’s philosophy is basically isomorphic to that of Husserl. Where Husserl speaks of the ego, Heidegger speaks of Dasein, where Husserl speaks of the noema, Heidegger speaks of the structure of Dasein’s Being-in-the-world and so on. Husserl also observed this. Several places in his copy of Being and Time Husserl wrote in the margin that Heidegger was just translating Husserl’s phenomenology into another terminology. Thus, for example, on page 13 Husserl wrote: “Heidegger transposes or transforms the constitutive phenomenological clarification of all realms of entities and universals, the total region World into the anthropological. The problematic is translation, to the ego corresponds Dasein etc. Thereby everything becomes deep-soundingly unclear, and philosophically it loses its value.” Similarly, on page 62, Husserl remarks: “What is said here is my own theory, but without a deeper justification.” (p. 369, my emphasis)

Heidegger and his terms have certainly been more popular and in wider use since then.

Føllesdal also highlights where the two philosophers diverge.2 In particular, Heidegger gives a central role to the role of the body and action in constituting the world. While in his publications Husserl stuck to a focus on how perception constitutes the Lifeworld, Heidegger uses many examples from action.3 Our action in the world, including our skillfulness in action constitutes those objects we interact with for us.

Heidegger contrasts two modes of being (in addition to our own mode — being-in-the-world): present-at-hand and ready-to-hand (or alternatively, the occurant and the available (Dreyfus 1990)). The former is the mode of being consideration of an object as a physical thing present to us — or occurant, and Heidegger argues it constitutes the narrow focus of previous philosophical explorations of being. The latter is the stuff of every skilled action — available for action: the object becomes equipment, which can often be transparent in action, such that it becomes an extension of our body.

J.J. Gibson expresses this view in his proposal of an ecological psychology (in which perception and action are closely linked):

When in use, a tool is a sort of extension of the hand, almost an attachment to it or a part of the user’s own body, and thus is no longer a part of the environment of the user. […] This capacity to attach something to the body suggests that the boundary between the animal and the environment is not fixed at the surface of the skin but can shift. More generally it suggests that the absolute duality of “objective” and “subjective” is false. When we consider the affordances of things, we escape this philosophical dichotomy. (1979, p. 41)

While there may be troubles ahead for this view, I think the passage captures well something we all can understand: when we use scissors, we feel the paper cutting; and when a blind person uses a cane to feel in front of them, they can directly perceive the layout of the surface in front of them.

Transparency, abstraction, opacity, intentionality

Research and design in HCI has sought at times to achieve this transparency, sometimes by drawing on our rich knowledge of and skill with the ordinary physical and social world. Metaphor in HCI (e.g., the desktop metaphor) can be seen as one widespread attempt at this (cf. Blackwell 2006). This kind of transparency does not throw abstraction out of the picture. Rather the two go hand-in-hand: the specific physical properties of the present-at-hand are abstracted away, with quickly perceived affordances for action in their place.

But other kinds of abstraction are in play in HCI as well. Interactive technologies can function as social actors and agents– with particular cues eliciting social responses that are normally applied to other people (Nass and Moon 2000, Fogg 2002). One kind of social response, not yet as widely considered in the HCI literature, is assuming the intentional stance — explanation in terms of beliefs, desires, hopes, fears, etc. — towards the system. This is a powerful, flexible, and easy predictive and explanatory strategy often also called folk psychology (Dennett 1987), which may be a tacit theory or a means of simulating other minds. We can explain other people based on what they believe and desire.

But we can also do the same for other things. To use one of Dennett’s classic examples, we can do the same for a thermostat: why did it turn the heat on? It wanted to keep the house at some level of warmth, it believed that it was becoming colder than desired, and it believed that it could make it warmer by turning on the heat. While in the case of the thermostat, this strategy doesn’t hide much complexity (we could explain it with other strategies without much trouble), it can be hugely useful when the system in question is complex or otherwise opaque to other kinds of description (e.g., it is a black box).

We might think then that perceived complexity and opacity should both be cues for adopting the intentional stance. But if the previous research on social responses to computers (not to mention the broader literature on heuristics and mindlessness) has taught us anything, it is that made objects such as computers can evoke unexpected responses through other simplier cues. Some big remaining questions that I hope to take up in future posts and research:

- What are these cues, both features of the system and situational factors?

- How can designers influence people to interpret and explain systems using folk psychology?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of evoking the intentional stance in users?

- How should we measure the use of the intentional stance?

- How is assuming the intentional stance towards a thing different (or the same) as it having being-in-the-world as its mode of being?

References

- But Husserl was Jewish, and Heidegger was himself a member of the Nazi party, so this did not happen in the first printing. [↩]

- Dreyfus (1990) is an alternative view that takes the divergence as quite radical; he sees Føllesdal as hugely underestimating the originality of Heidegger’s thought. Instead Dreyfus characterizes Husserl as formulating so clearly the Cartesian worldview that Heidegger recognized its failings and was thus able to radically and successfully critique it. [↩]

- It is worth noting that Husserl actually wrote about this as well, but in manuscripts, which Heidegger read years before writing Being and Time. [↩]