Marshaling the black ants: Practical knowledge in a small village in Malaysia

One of my favorite bits from James Scott’s Seeing Like a State:

While doing fieldwork in a small village in Malaysia, I was constantly struck by the breadth of my neighbors’ skills and their casual knowledge of local ecology. One particular anecdote is representative. Growing in the compound of the house in which I lived was a locally famous mango tree. Relatives and acquaintances would visit when the fruit was ripe in the hope of being given a few fruits and, more important, the chance to save and plant the seeds next to their own house. Shortly before my arrival, however, the tree had become infested with large red ants, which destroyed most of the fruit before it could ripen. It seemed nothing could be done short of bagging each fruit. Several times I noticed the elderly head of household, Mat Isa, bringing dried nipah palm fronds to the base of the mango tree and checking them. When I finally got around to asking what he was up to, he explained it to me, albeit reluctantly, as for him this was pretty humdrum stuff compared to our usual gossip. He knew that small black ants, which had a number of colonies at the rear of the compound, were the enemies of large red ants. He also knew that the thin, lancelike leaves of the nipah palm curled into long, tight tubes when they fell from the tree and died. (In fact, the local people used the tubes to roll their cigarettes.) Such tubes would also, he knew, be ideal places for the queens of the black ant colonies to lay their eggs. Over several weeks he placed dried nipah fronds in strategic places until he had masses of black-ant eggs beginning to hatch. He then placed the egg-infested fronds against the mango tree and observed the ensuing week-long Armageddon. Several neighbors, many of them skeptical, and their children followed the fortunes of the ant war closely. Although smaller by half or more, the black ants finally had the weight of numbers to prevail against the red ants and gain possession of the ground at the base of the mango tree. As the black ants were not interested in the mango leaves or fruits while the fruits were still on the tree, the crop was saved.

This successful field experiment in biological controls presupposes several kinds of knowledge: the habitat and diet of black ants, their egg-laying habits, a guess about what local material would substitute as movable egg chambers, and experience with the fighting proclivities of red and black ants. Mat Isa made it clear that such skill in practical entomology was quite widespread, at least among his older neighbors, and that people remembered something like this strategy having worked once or twice in the past. What is clear to me is that no agricultural extension official would have known the first thing about ants, let alone biological controls; most extension agents were raised in town and in any case were concerned entirely with rice, fertilizer, and loans. Nor would most of them think to ask; they were, after all, the experts, trained to instruct the peasant. It is hard to imagine this knowledge being created and maintained except in the context of lifelong observation and a relatively stable, multigenerational community that routinely exchanges and preserves knowledge of this kind. [Chapter 9]

Is thinking about monetization a waste of our best minds?

I just recently watched this talk by Jack Conte, musician, video artist, and cofounder of Patreon:

Jack dives into how rapidly the Internet has disrupted the business of selling reproducible works, such as recorded music, investigative reporting, etc. And how important — and exciting — it is build new ways for the people who create these works to be able to make a living doing so. Of course, Jack has some particular ways of doing that in mind — such as subscriptions and subscription-like patronage of artists, such as via Patreon.

But this also made me think about this much-repeated1 quote from Jeff Hammerbacher (formerly of Facebook, Cloudera, and now doing bioinformatics research):

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.”

I certainly agree that many other types of research can be very important and impactful, and often more so than working on data infrastructure, machine learning, market design, etc. for advertising. However, Jack Conte’s talk certainly helped make the case for me that monetization of “content” is something that has been disrupted already but needs some of the best minds to figure out new ways for creators of valuable works to make money.

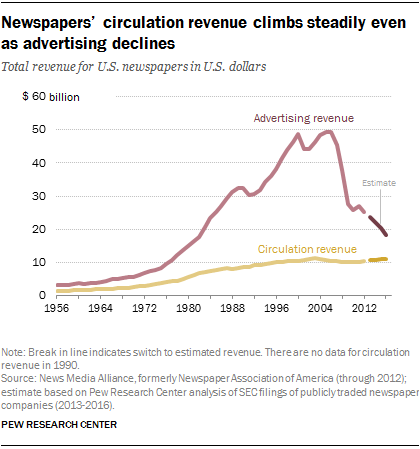

Some of this might be coming up with new arrangements altogether. But it seems like this will continue to occur partially through advertising revenue. Jack highlights how little ad revenue he often saw — even as his videos were getting millions of views. And newspapers’ have been less able to monetize online attention through advertising than they had been able to in print.

Some of this may reflect that advertising dollars were just really poorly allocated before. But improving this situation will require a mix of work on advertising — certainly beyond just getting people to click on ads — such as providing credible measurement of the effects and ROI of advertising, improving targeting of advertising, and more.

Another side of this question is that advertising remains an important part of our culture and force for attitude and behavior change. Certainly looking back on 2016 right now, many people are interested in what effects political advertising had.

So maybe it isn’t so bad if at least some of our best minds are working on online advertising.

- So often repeated that Hammerbacher said to Charlie Rose, “That’s going to be on my tombstone, I think.” [↩]

Will the desire for other perspectives trump the “friendly world syndrome”?

Some recent journalism at NPR and The New York Times has addressed some aspects of the “friendly world syndrome” created by personalized media. A theme common to both pieces is that people want to encounter different perspectives and will use available resources to do so. I’m a bit more skeptical.

If we keep seeing the same links and catchphrases ricocheting around our social networks, it might mean we are being exposed only to what we want to hear, says Damon Centola, an assistant professor of economic sociology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“You might say to yourself: ‘I am in a group where I am not getting any views other than the ones I agree with. I’m curious to know what else is out there,’” Professor Centola says.

Consider a new hashtag: diversity.

This is how Singer ends this article in which the central example is “icantdateyou” leading Egypt-related idioms as a trending topic on Twitter. The suggestion here, by Centola and Singer, is that people will notice they are getting a biased perspective of how many people agree with them and what topics people care about — and then will take action to get other perspectives.

Why am I skeptical?

First, I doubt that we really realize the extent to which media — and personalized social media in particular — bias their perception of the frequency of beliefs and events. Even though people know that fiction TV programs (e.g., cop shows) don’t aim to represent reality, heavy TV watchers (on average) substantially overestimate the percent of adult men employed in law enforcement.1 That is, the processes that produce the “friendly world syndrome” function without conscious awareness and, perhaps, even despite it. So people can’t consciously choose to seek out diverse perspectives if they don’t know they are increasingly missing them.

Second, I doubt that people actually want diversity of perspectives all that much. Even if I realize divergent views are missing from my media experience, why would I seek them out? This might be desirable for some people (but not all), and even for those, the desire to encounter people who radically disagree has its limits.

Similar ideas pop up in a NPR All Things Considered segment by Laura Sydell. This short piece (audio, transcript) is part of NPR’s “Cultural Fragmentation” series.2 The segment begins with the worry that offline bubbles are replicated online and quotes me describing how attempts to filter for personal relevance also heighten the bias towards agreement in personalized media.

But much of the piece has actually focuses on how one person — Kyra Gaunt, a professor and musician — is using Twitter to connect and converse with new and different people. Gaunt describes her experience on Twitter as featuring debate, engagement, and “learning about black people even if you’ve never seen one before”. Sydell’s commentary identifies the public nature of Twitter as an important factor in facilitating experiencing diverse perspectives:

But, even though there is a lot of conversation going on among African Americans on Twitter, Professor Gaunt says it’s very different from the closed nature of Facebook because tweets are public.

I think this is true to some degree: much of the content produced by Facebook users is indeed public, but Facebook does not make it as easily searchable or discoverable (e.g., through trending topics). But more importantly, Facebook and Twitter differ in their affordances for conversation. Facebook ties responses to the original post, which means both that the original poster controls who can reply and that everyone who replies is part of the same conversation. Twitter supports replies through the @reply mechanism, so that anyone can reply but the conversation is fragmented, as repliers and consumers often do not see all replies. So, as I’ve described, even if you follow a few people you disagree with on Twitter, you’ll most likely see replies from the other people you follow, who — more often than not — you agree with.

Gaunt’s experience with Twitter is certainly not typical. She has over 3,300 followers and follows over 2,400, so many of her posts will generate replies from people she doesn’t know well but whose replies will appear in her main feed. And — if she looks beyond her main feed to the @Mentions page — she will see the replies from even those she does not follow herself. On the other hand, her followers will likely only see her posts and replies from others they follow.3

Nonetheless, Gaunt’s case is worth considering further, as does Sydell:

SYDELL: Gaunt says she’s made new friends through Twitter.

GAUNT: I’m meeting strangers. I met with two people I had engaged with through Twitter in the past 10 days who I’d never met in real time, in what we say in IRL, in real life. And I met them, and I felt like this is my tribe.

SYDELL: And Gaunt says they weren’t black. But the key word for some observers is tribe. Although there are people like Gaunt who are using social media to reach out, some observers are concerned that she is the exception to the rule, that most of us will be content to stay within our race, class, ethnicity, family or political party.

So Professor Gaunt is likely making connections with people she would not have otherwise. But — it is at least tempting to conclude from “this is my tribe” — they are not people with radically different beliefs and values, even if they have arrived at those beliefs and values from a membership in a different race or class.

- Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “Mainstreaming” of America: Violence Profile No. 11. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10-29. [↩]

- I was also interviewed for the NPR segment. [↩]

- One nice feature in “new Twitter” — the recently refresh of the Twitter user interface — is that clicking on a tweet will show some of the replies to it in the right column. This may offer an easier way for followers to discover diverse replies to the people they follow. But it is also not particularly usable, as it is often difficult to even trace what a reply is a reply to. [↩]

Ideas behind their time: formal causal inference?

Alex Tabarrok at Marginal Revolution blogs about how some ideas seem notably behind their time:

We are all familiar with ideas said to be ahead of their time, Babbage’s analytical engine and da Vinci’s helicopter are classic examples. We are also familiar with ideas “of their time,” ideas that were “in the air” and thus were often simultaneously discovered such as the telephone, calculus, evolution, and color photography. What is less commented on is the third possibility, ideas that could have been discovered much earlier but which were not, ideas behind their time.

In comparing ideas behind and ahead of their times, it’s worth considering the processes that identify them as such.

In the case of ideas ahead of their time, we rely on records and other evidence of their genesis (e.g., accounts of the use of flamethrowers at sea by the Byzantines ). Later users and re-discoverers of these ideas are then in a position to marvel at their early genesis. In trying to see whether some idea qualifies as ahead of its time, this early genesis, lack or use or underuse, followed by extensive use and development together serve as evidence for “ahead of its time” status.

On the other hand, in identifying ideas behind their time, it seems that we need different sorts of evidence. Taborrok uses the standard of whether their fruits could have been produced a long time earlier (“A lot of the papers in say experimental social psychology published today could have been written a thousand years ago so psychology is behind its time”). We need evidence that people in a previous time had all the intellectual resources to generate and see the use of the idea. Perhaps this makes identifying ideas behind their time harder or more contentious.

Y(X = x) and P(Y | do(x))

Perhaps formal causal inference — and some kind of corresponding new notation, such as Pearl’s do(x) operator or potential outcomes — is an idea behind its time.1 Judea Pearl’s account of the history of structural equation modeling seems to suggest just this: exactly what the early developers of path models (Wright, Haavelmo, Simon) needed was new notation that would have allowed them to distinguish what they were doing (making causal claims with their models) from what others were already doing (making statistical claims).2

In fact, in his recent talk at Stanford, Pearl suggested just this — that if the, say, the equality operator = had been replaced with some kind of assignment operator (say, :=), formal causal inference might have developed much earlier. We might be a lot further along in social science and applied evaluation of interventions if this had happened.

This example raises some questions about the criterion for ideas behind their time that “people in a previous time had all the intellectual resources to generate and see the use of the idea” (above). Pearl is a computer scientist by training and credits this background with his approach to causality as a problem of getting the formal language right — or moving between multiple formal languages. So we may owe this recent development to comfort with creating and evaluating the qualities of formal languages for practical purposes — a comfort found among computer scientists. Of course, e.g., philosophers and logicians also have been long comfortable with generating new formalisms. I think of Frege here.

So I’m not sure whether formal causal inference is an idea behind its time (or, if so, how far behind). But I’m glad we have it now.

- There is a “lively” debate about the relative value of these formalisms. For many of the dense causal models applicable to the social sciences (everything is potentially a confounder), potential outcomes seem like a good fit. But they can become awkward as the causal models get complex, with many exclusion restrictions (i.e. missing edges). [↩]

- See chapter 5 of Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference. 2nd Ed. Cambridge University Press. [↩]

Public once, public always? Privacy, egosurfing, and the availability heuristic

The Library of Congress has announced that it will be archiving all Twitter posts (tweets). You can find positive reaction on Twitter. But some have also wondered about privacy concerns. Fred Stutzman, for example, points out how even assuming that only unprotected accounts are being archived this can still be problematic.1 While some people have Twitter usernames that easily identify their owners and many allow themselves to be found based on an email address that is publicly associated with their identity, there are also many that do not. If at a future time, this account becomes associated with their identity for a larger audience than they desire, they can make their whole account viewable only by approved followers2, delete the account, or delete some of the tweets. Of course, this information may remain elsewhere on the Internet for a short or long time. But in contrast, the Library of Congress archive will be much more enduring and likely outside of individual users’ control.3 While I think it is worth examining the strategies that people adopt to cope with inflexible or difficult to use privacy controls in software, I don’t intend to do that here.

Instead, I want to relate this discussion to my continued interest in how activity streams and other information consumption interfaces affect their users’ beliefs and behaviors through the availability heuristic. In response to some comments on his first post, Stutzman argues that people overestimate the degree to which content once public on the Internet is public forever:

So why is it that we all assume that the content we share publicly will be around forever? I think this is a classic case of selection on the dependent variable. When we Google ourselves, we are confronted with what’s there as opposed to what’s not there. The stuff that goes away gets forgotten, and we concentrate on things that we see or remember (like a persistent page about us that we don’t like). In reality, our online identities decay, decay being a stochastic process. The internet is actually quite bad at remembering.

This unconsidered “selection on the dependent variable” is one way of thinking about some cases of how the availability heuristic (and use of ease-of-retrievel information more generally). But I actually think the latter is more general and more useful for describing the psychological processes involved. For example, it highlights both that there are many occurrences or interventions can can influence which cases are available to mind and that even if people have thought about cases where their content disappeared at some point, this may not be easily retrieved when making particular privacy decisions or offering opinions on others’ actions.

Stutzman’s example is but one way that the combination of the availability heuristic and existing Internet services combine to affect privacy decisions. For example, consider how activity streams like Facebook News Feed influence how people perceive their audience. News Feed shows items drawn from an individual’s friends’ activities, and they often have some reciprocal access. However, the items in the activity stream are likely unrepresentative of this potential and likely audience. “Lurkers” — people who consume but do not produce — are not as available to mind, and prolific producers are too available to mind for how often they are in the actual audience for some new shared content. This can, for example, lead to making self-disclosures that are not appropriate for the actual audience.

- This might not be the case, see Michael Zimmer and this New York Times article. [↩]

- Why don’t people do this in the first place? Many may not be aware of the feature, but even if they are, there are reasons not to use it. For example, it makes any participation in topical conversations (e.g., around a hashtag) difficult or impossible. [↩]

- Or at least this control would have to be via Twitter, likely before archiving: “We asked them [Twitter] to deal with the users; the library doesn’t want to mediate that.” [↩]