Not just predicting the present, but the future: Twitter and upcoming movies

Search queries have been used recently to “predict the present“, as Hal Varian has called it. Now some initial use of Twitter chatter to predict the future:

The chatter in Twitter can accurately predict the box-office revenues of upcoming movies weeks before they are released. In fact, Tweets can predict the performance of films better than market-based predictions, such as Hollywood Stock Exchange, which have been the best predictors to date. (Kevin Kelley)

Here is the paper by Asur and Huberman from HP Labs. Also see a similar use of online discussion forums.

But the obvious question from my previous post is, how much improvement do you get by adding more inputs to the model? That is, how does the combined Hollywood Stock Exchange and Twitter chatter model perform? The authors report adding the number of theaters the movie opens in to both models, but not combining them directly.

Search terms and the flu: preferring complex models

Simplicity has its draws. A simple model of some phenomena can be quick to understand and test. But with the resources we have today for theory building and prediction, it is worth recognizing that many phenomena of interest (e.g., in social sciences, epidemiology) are very, very complex. Using a more complex model can help. It’s great to try many simple models along the way — as scaffolding — but if you have a large enough N in an observational study, a larger model will likely be an improvement.

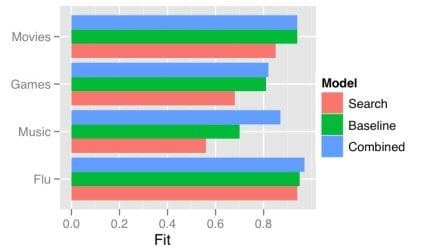

One obvious way a model gets more complex is by adding predictors. There has recently been a good deal of attention on using the frequency of search terms to predict important goings-on — like flu trends. Sharad Goel et al. (blog post, paper) temper the excitement a bit by demonstrating that simple models using other, existing public data sets outperform the search data. In some cases (music popularity, in particular), adding the search data to the model improves predictions: the more complex combined model can “explain” some of the variance not handled by the more basic non-search-data models.

This echos one big takeaway from the Netflix Prize competition: committees win. The top competitors were all large teams formed from smaller teams and their models were tuned combinations of several models. That is, the strategy is, take a bunch of complex models and combine them.

One way of doing this is just taking a weighted average of the predictions of several simpler models. This works quite well when your measure of the value of your model is root mean squared error (RMSE), since RMSE is convex.

While often the larger model “explains” more of the variance, what “explains” means here is just that the R-squared is larger: less of the variance is error. More complex models can be difficult to understand, just like the phenomena they model. We will continue to need better tools to understand, visualize, and evaluate our models as their complexity increases. I think the committee metaphor will be an interesting and practical one to apply in the many cases where the best we can do is use a weighted average of several simpler, pretty good models.

Multitasking among tasks that share a goal: action identification theory

Right from the start of today’s Media Multitasking Workshop1, it’s clear that one big issue is just what people are talking about when they talk about multitasking. In this post, I want to highlight the relationship between defining different kinds of multitasking and people’s representations of the hierarchical structure of action.

It is helpful to start with a contrast between two kinds of cases.

Distributing attention towards a single goal

In the first, there is a single task or goal that involves dividing one’s attention, with the targets of attention somehow related, but of course somewhat independent. Patricia Greenfield used Pac-Man as an example: each of the ghosts must be attended to (in addition to Pac-Man himself), and each is moving independently, but each is related to the same larger goal.

Distributing attention among different goals

In the second kind of case, there are two completely unrelated tasks that divide attention, as in playing a game (e.g., solitaire) while also attending to a speech (e.g., in person, on TV). Anthony Wagner noted that in Greenfield’s listing of the benefits and costs of media multitasking, most of the listed benefits applied to the former case, while the costs she listed applied to the later. So keeping these different senses of multitasking straight is important.

Complications

But the conclusion should not be to think that this is a clear and stable distinction that slices multitasking phenomena in just the right way. Consider one ways of putting this distinction: the primary and secondary task can either be directed at the same goal or directed at different goals (or tasks). Let’s dig into this a bit more.2

Byron Reeves pointed out that sometimes “the IMing is about the game.” So we could distinguish whether the goal of the IMing is the same as the goal of the in-game task(s). But this making this kind of distinction requires identity conditions for goals or tasks that enable this distinction. As Ulrich Mayr commented, goals can be at many different levels, so in order to use goal identity as the criterion, one has to select a level in the hierarchy of goals.

Action identities and multitasking

We can think about this hierarchy of goals as the network of identities for an action that are connected with the “by” relation: one does one thing by doing (several) other things. If these goals are the goals of the person as they represent them, then this is the established approach taken by action identification theory (Vallacher & Wegner, 1987) — and this could be valuable lens for thinking about this. Action identification theory claims that people can report an action identity for what they are doing, and that this identity is the “prepotent identity”. This prepotent identity is generally the highest level identity under which the action is maintainable. This means that the prepotent identity is at least somewhat problematic if used to make this distinction between these two types of multitasking because then the distinction would be dependent on, e.g., how automatic or functionally transparent the behaviors involved are.

For example, if I am driving a car and everything is going well, I may represent the action as “seeing my friend Dave”. I may also represent my simultaneous, coordinating phone call with Dave under this same identity. But if driving becomes more difficult, then my prepotent identity will decrease in level in order to maintain the action. Then these two tasks would not share the prepotent action identity.

Prepotent action identities (i.e. the goal of the behavior as represented by the person in the moment) do not work to make this distinction for all uses. But I think that it actually does help makes some good distinctions about the experience of multitasking, especially if we examine change in action identities over time.

To return to case of media multitasking, consider the headline ticker on 24-hour news television. The headline ticker can be more or less related to what the talking heads are going on about. This could be evaluated as a semantic, topical relationship. But considered as a relationship of goals — and thus action identities — we can see that perhaps sometimes the goals coincide even when the content is quite different. For example, my goal may simply to be “get the latest news”, and I may be able to actually maintain this action — consuming both the headline ticker and the talking heads’ statements — under this high level identity. This is an importantly different case then if I don’t actually maintain the action at the level, but instead must descend to — and switch between — two (or more) lower level identities that are associated the two streams of content.

References

Vallacher, R. R., & Wegner, D. M. (1987). What do people think they’re doing? Action identification and human behavior. Psychological Review, 94(1), 3-15.

- The full name is the “Seminar on the impacts of media multitasking on children’s learning and development”. [↩]

- As I was writing this, the topic re-emerged in the workshop discussion. I made some comments, but I think I may not have made myself clear to everyone. Hopefully this post is a bit of an improvement. [↩]

Social and cultural costs of media multitasking

Today I’m attending the Media Multitasking workshop at Stanford. I’m going to just blog as I go, so these posts are going to perhaps be a bit rougher than usual.1

The workshop began with a short keynote from Patricia Greenfield, a psychology professor at UCLA, about the costs and benefits of media multitasking. Greenfield’s presentation struck me as representing as an essentially conservative and even alarmist perspective on media multitasking.

Exemplifying this perspective was Greenfield’s claim that media multitasking (by children) is disrupting family rituals and privileging peer interaction over interaction with family. Greenfield mixed in some examples of how having a personal mobile phone allows teens to interact with peers without their parents being in the loop (e.g., aware of who their children’s interaction partners are). These examples don’t strike me as particularly central to understanding media multitasking; instead, they highlight the pervasive alarmism about new media and remind me of how “helicopter parents'” extreme control of their children’s physical co-presence with others is also a change from “how things used to be”.

Face-to-face vs. mediated

The relationship of these worries about mobile phones and the allegedly decreasing control that parents have over their children’s social interaction to media multitasking is that mediated communication is being privileged over face-to-face interaction. Greenfield proposed that face-to-face interaction suffers from media use and media multi-tasking, and that this is worrisome because we have evolved for face-to-face interaction. She commented that face-to-face interaction enables empathy; there is an implicit contrast here with mediated interaction, but I’m not sure it is so obvious that mediated communication doesn’t enable empathy — including empathizing with targets that one would otherwise not encounter face-to-face and experiencing a persistent shared perspective with close, but distant, others (e.g., parents and college student children).

Family reunion

Greenfield cited a study of 30 homes in which children and a non-working parent only greeted the other parent returning home from work about one third of the time (Ochs et al., 2006), arguing — as I understood it — that this is symptomatic of a deprioritization of face-to-face interaction.

As another participant pointed out, this could also — if not in these particular cases, then likely in others — be a case of not feeling apart during the working day: that is, we can ask, are the children and non-working parents communicating with the parent during the workday? In fact, Ochs et al. (2006, pp. 403-4) presents an example of such a reunion (between husband and wife in this case) in which the participants have been in contact by mobile phone, and the conversation picks up where it left off (with the addition of some new information available by being present in the home).

Next

I’m looking forward to the rest of the workshop. I think one clear theme of the workshop is going to be differing emphasis on costs and benefits of media multitasking of different types. I expect Greenfield’s “doom and gloom” will continue to be contrasted with other perspectives — some of which already came up.

References

Ochs, E., Graesch, A. P., Mittmann, A., Bradbury, T., & Repetti, R. (2006). Video ethnography and ethnoarchaeological tracking. The Work and Family Handbook: Multi-Disciplinary Perspective, Methods, and Approaches, 387–409.

- Which also means I’m multitasking, in some senses, through the whole conference. [↩]

Etching by Da Vinci? Representing legend, culture, and language

- A photo I took in Piazza della Signoria of an etching, reportedly a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci that he etched behind his back on a dare onto the side of the Palazzo Vecchio.

Is this etching a self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci created hundreds of years ago? That’s what I was told by a Californian friend who had “gone native” in Florence. Another matter: is this, in fact, a commonly believed and shared legend, and what other variations are there on it?

I shared the story with some fellow visitors in Florence on a lunch-time return to the piazza. Ed Chi tried to verify the rumor using a Web search, but with no success. At least in English, there didn’t seem to be much on this in the Web. (See my photo and comments on Flickr.)

I posted the photo on Flickr. I asked questions on LinkedIn and Yahoo! Answers, with no success. I also asked for help from workers on Mechanical Turk. Here’s part of how I asked for help:

There is a portrait etched in stone on the wall of Palazzo Vecchio in Piazza della Signoria in Florence (Firenza), Italy. It is close behind the copy of the David there. I have heard that there is a legend that this is a self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci. I am looking for any information about this legend, alternate versions of the legend, or information about the real source of the portrait.

What results have been offered seem to suggest that this legend exists — though perhaps it is “actually” (at least as captured online, since perhaps the Leonardo theorists aren’t as active digital content creators) about Michelangelo:

- Palazzo Vecchio in Italian Wikipedia

- Florentine Legends: Fact or Fiction (in Italian)

- Curiosities in Florence

The best way of finding out seemed to actually be my Flickr photo itself, since that’s where Daniel Witting provided the first two links above — however, this was a few months after the photo was first posted to Flickr. Turkers provided a couple useful links also (“Curiosities” above) on a shorter schedule and with a higher price. (I should have also tried uClue — where many former Google Answers researchers now work. This was recommended by Max Harper, who has studied Q&A sites in detail.)

–

Question and answer services along the lines of Yahoo! Answers rose to global (and U.S.) significance only after success in Korea, where Naver Knowledge iN pioneered the use of an online community to power a Q&A site. A major motivation Korea was the limited amount of Korean content online. With Naver’s offering, Korea’s Internet saavy, English population made information newly available in Korean (and did plenty of other interesting work).

This is as significant a motivation for Q&A sites by English-speaking folks in the U.S., but the present case is an exception.

Some of the questions that made this case interesting to me:

- What culturally-shared beliefs get manifest online? During this whole process, I and others wondered whether perhaps this local legend was only shared orally. It seems that it is represented online after all — at least the Michelangelo variant, but it could have been otherwise.

- How does the pair of languages a task requires knowledge of determine the processes, structres, and communities that are optimal for completing the task? For example, it seems quite important whether the target or source language has many more speakers than the other. (One could think about this simplistically in terms of conditional probabilities of skills with language A given skill with language B and vice verse.)