Etching by Da Vinci? Representing legend, culture, and language

- A photo I took in Piazza della Signoria of an etching, reportedly a self-portrait of Leonardo da Vinci that he etched behind his back on a dare onto the side of the Palazzo Vecchio.

Is this etching a self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci created hundreds of years ago? That’s what I was told by a Californian friend who had “gone native” in Florence. Another matter: is this, in fact, a commonly believed and shared legend, and what other variations are there on it?

I shared the story with some fellow visitors in Florence on a lunch-time return to the piazza. Ed Chi tried to verify the rumor using a Web search, but with no success. At least in English, there didn’t seem to be much on this in the Web. (See my photo and comments on Flickr.)

I posted the photo on Flickr. I asked questions on LinkedIn and Yahoo! Answers, with no success. I also asked for help from workers on Mechanical Turk. Here’s part of how I asked for help:

There is a portrait etched in stone on the wall of Palazzo Vecchio in Piazza della Signoria in Florence (Firenza), Italy. It is close behind the copy of the David there. I have heard that there is a legend that this is a self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci. I am looking for any information about this legend, alternate versions of the legend, or information about the real source of the portrait.

What results have been offered seem to suggest that this legend exists — though perhaps it is “actually” (at least as captured online, since perhaps the Leonardo theorists aren’t as active digital content creators) about Michelangelo:

- Palazzo Vecchio in Italian Wikipedia

- Florentine Legends: Fact or Fiction (in Italian)

- Curiosities in Florence

The best way of finding out seemed to actually be my Flickr photo itself, since that’s where Daniel Witting provided the first two links above — however, this was a few months after the photo was first posted to Flickr. Turkers provided a couple useful links also (“Curiosities” above) on a shorter schedule and with a higher price. (I should have also tried uClue — where many former Google Answers researchers now work. This was recommended by Max Harper, who has studied Q&A sites in detail.)

–

Question and answer services along the lines of Yahoo! Answers rose to global (and U.S.) significance only after success in Korea, where Naver Knowledge iN pioneered the use of an online community to power a Q&A site. A major motivation Korea was the limited amount of Korean content online. With Naver’s offering, Korea’s Internet saavy, English population made information newly available in Korean (and did plenty of other interesting work).

This is as significant a motivation for Q&A sites by English-speaking folks in the U.S., but the present case is an exception.

Some of the questions that made this case interesting to me:

- What culturally-shared beliefs get manifest online? During this whole process, I and others wondered whether perhaps this local legend was only shared orally. It seems that it is represented online after all — at least the Michelangelo variant, but it could have been otherwise.

- How does the pair of languages a task requires knowledge of determine the processes, structres, and communities that are optimal for completing the task? For example, it seems quite important whether the target or source language has many more speakers than the other. (One could think about this simplistically in terms of conditional probabilities of skills with language A given skill with language B and vice verse.)

Motivations for tagging: organization and communication motives on Facebook

Increasing valuable annotation behaviors was a practical end of a good deal of work at Yahoo! Research Berkeley. ZoneTag is a mobile application and service that suggests tags when users choose to upload a photo (to Flickr) based on their past tags, the relevant tags of others, and events and places nearby. Through social influence and removing barriers, these suggestions influence users to expand and consistently use their tagging vocabulary (Ahern et al. 2006).

Context-aware suggestion techniques such as those used in ZoneTag can increase tagging, but what about users’ motivations for considering tagging in the first place? And how can these motivations for annotation be considered in designing services that involve annotation? In this post, I consider existing work on motivations for tagging, and I use tagging on Facebook as an example of how multiple motivations can combine to increase desired annotation behaviors.

Using photo-elicitation interviews with ZoneTag users who tag, Ames & Naaman (2007) present a two factor taxonomy of motivations for tagging. First, they categorize tagging motivations by function: is the motivating function of the tagging organizational or communicative? Organizational functions include supporting search, presenting photos by event, etc., while communicative functions include when tags provide information about the photos, their content, or are otherwise part of a communication (e.g., telling a joke). Second, they categorize tagging motivations by intended audience (or sociality): are the tags intended for my future self, people known to me (friends, family, coworkers, online contacts), or the general public?

On Flickr the function dimension generally maps onto the distinction between functionality that enables and is prior to arriving at the given photo or photos (organization) and functionality applicable once one is viewing a photo (communication). For example, I can find a photo (by me or someone else) by searching for a person’s name, and then use other tags applied to that photo to jog my memory of what event the photo was taken at.

Some Flickr users subscribe to RSS feeds for public photos tagged with their name, making for a communication function of tagging — particularly tagging of people in media — that is prior to “arriving” at a specific media object. These are generally techie power users, but this can matter for others. Some less techie participants in our studies reported noticing that their friends did this — so they became aware of tagging those friends’ names as a communicative act that would result in the friends finding the tagged photos.

This kind of function of tagging people is executed more generally — and for more than just techie power users — by Facebook. In tagging of photos, videos, and blog posts, tagging a person notifies them they have been tagged, and can add that they have been tagged to their friends’ News Feeds. This function has received a lot of attention from a privacy perspective (and it should). But I think it hints at the promise of making annotation behavior fulfill more of these functions simultaneously. When specifying content can also be used to specify recipients, annotation becomes an important trigger for communication.

—————

See some interesting comments (from Twitter) about tagging on Facebook:

- noticing people tagging to gain eyeballs

- exhorting others not to tag bad photos (and thanks)

- collapsing time by tagging photos from long ago

- tagging by parents

(Also see Facebook’s growing use and testing of autotagging [1, 2].)

References

Ames, M., & Naaman, M. (2007). Why we tag: motivations for annotation in mobile and online media. In Proceedings of CHI 2007 (pp. 971-980). San Jose, California, USA: ACM.

Ahern, S., Davis, M., Eckles, D., King, S., Naaman, M., Nair, R., et al. (2006). Zonetag: Designing context-aware mobile media capture to increase participation. Pervasive Image Capture and Sharing: New Social Practices and Implications for Technology Workshop. In Adjunct Proc. Ubicomp 2006.

Activity streams, personalization, and beliefs about our social neighborhood

Every person who logs into Facebook is met with the same interface but with personalized content. This interface is News Feed, which lists “news stories” generated by users’ Facebook friend. These news stories include the breaking news that Andrew was just tagged in a photo, that Neema declared he is a fan of a particular corporation, that Ellen joined a group expressing support for a charity, and that Alan says, “currently enjoying an iced coffee… anyone want to see a movie tonight?”

News Feed is an example of a particular design pattern that has recently become quite common – the activity stream. An activity stream aggregates actions of a set of individuals – such as a person’s egocentric social network – and displays the recent and/or interesting ones.

I’ve previously analysed, in a more fine-grained analysis of a particular (and now changed) interface element for setting one’s Facebook status message, how activity streams bias our beliefs about the frequency of others’ participation on social network services (SNSs). It works like this:

- We use availability to mind as a heuristic for estimating probability and frequency (Kahneman & Tversky, 1973). So if it is easier to think of a possibility, we judge it to be more likely or frequent. This heuristic is often helpful, but it also leads to bias due to, e.g., recent experience, search strategy (compare thinking of words starting with ‘r’ versus words with ‘r’ as the third letter).

- Activity streams show a recent subset of the activity available (think for now of a simple activity stream, like that on one’s Twitter home page).

- Activity streams show activity that is more likely to be interesting and is more likely to have comments on it.

Through the availability heuristic (and other mechanisms) this leads to one to estimate that (1) people in one’s egocentric network are generating activity on Facebook more frequently than they actually are and (2) stories with particular characteristics (e.g., comments on them) are more (or less) common in one’s egocentric network than they actually are.

Personalized cultivation

When thinking about this in the larger picture, one can see this as a kind of cultivation effect of algorithmic selection processes in interpersonal media. According to cultivation theory (see Williams, 2006, for an application to MMORGs), our long-term exposure to media makes leads us to see the real world through the lens of the media world; this exposure gradually results in beliefs about the world based on the systematic distortions of the media world (Gerbner et al., 1980). For example, heavy television viewing predicts giving more “television world” answers to questions — overestimating the frequency of men working in law enforcement and the probability of experiencing violent acts. A critical difference here is that with activity streams, similar cultivation can occur with regard to our local social and cultural neighborhood.

Aims of personalization

Automated personalization has traditionally focused on optimizing for relevance – keep users looking, get them clicking for more information, and make them participate related to this relevant content. But the considerations here highlight another goal of personalization: personalization for strategic influence on attitudes that matter for participation. These goals can be in tension. For example, should the system present…

The most interesting and relevant photos to a user?

Showing photographs from a user’s network that have many views and comments may result in showing photos that are very interesting to the user. However, seeing these photos can lead to inaccurate beliefs about how common different kinds of photos are (for example, overestimating the frequency of high-quality, artistic photos and underestimating the frequency of “poor-quality” cameraphone photos). This can discourage participation through perceptions of the norms for the network or the community.

On the other hand, seeing photos with so many comments or views may lead to overestimating how many comments one is likely to get on one’s own photo; this can result in disappointment following participation.

Activity from a user’s closest friends?

Assume that activity from close friends is more likely to be relevant and interesting. It might even be more likely to prompt participation, particularly in the form of comments and replies. But it can also bias judgments of likely audience: all those people I don’t know so well are harder to bring to mind as is, but if they don’t appear much in the activity stream for my network, I’m less likely to consider them when creating my content. This could lead to greater self-disclosure, bad privacy experiences, poor identity management, and eventual reduction in participation.

References

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N. (1980). The “Mainstreaming” of America: Violence Profile No. 11. Journal of Communication, 30(3), 10-29.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5, 207-232.

Williams, D. (2006). Virtual Cultivation: Online Worlds, Offline Perceptions. Journal of Communication, 56, 69-87.

Transformed social interaction and actively mediated communication

Transformed social interaction (TSI) is modification, filtering, and synthesis of representations of face-to-face communication behavior, identity cues, and sensing in a collaborative virtual environment (CVE): TSI flexibly and strategically decouples representation from behavior. In this post, I want to extend this notion of TSI, as presented in Bailenson et al. (2005), in two general ways. We have begun calling the larger category actively mediated communication.1

First, I want to consider a larger category of strategic mediation in which no communication behavior is changed or added between different existing participants. This includes applying influence strategies to the feedback to the communicator as in coaching (e.g., Kass 2007) and modification of the communicator’s identity as presented to himself (i.e. the transformations of the Proteus effect). This extension entails a kind of unification of TSI with persuasive technology for computer-mediated communication (CMC; Fogg 2002, Oinas-Kukkonen & Harjumaa 2008).

Second, I want to consider a larger category of media in which the same general ideas of TSI can be manifest, albeit in quite different ways. As described by Bailenson et al. (2005), TSI is (at least in exemplars) limited to transformations of representations of the kind of non-verbal behavior, sensing, and identity cues that appear in face-to-face communication, and thus in CVEs. I consider examples from other forms of communication, including active mediation of the content, verbal or non-verbal, of a communication.

Feedback and influence strategies: TSI and persuasive technology

TSI is exemplified by direct transformation that is continuous and dynamic, rather than, e.g., static anonymization or pseudonymization. These transformations are complex means to strategic ends, and they function through a “two-step” programmatic-psychological process. For example, a non-verbal behavior is changed (modified, filtered, replaced), and then the resulting representation affects the end through a psychological process in other participants. Similar ends can be achieved by similar means in the second (psychological) step, without the same kind of direct programmatic change of the represented behavior.

In particular, consider coaching of non-verbal behavior in a CVE, a case already considered as an example of TSI (Bailenson et al. 2005, pp. 434-6), if not a particularly central one. In one case, auxiliary information is used to help someone interact more successfully:

In those interactions, we render the interactants’ names over their heads on floating billboards for the experimenter to read. In this manner the experimenter can refer to people by name more easily. There are many other ways to use these floating billboards to assist interactants, for example, reminders about the interactant’s preferences or personality (e.g., “doesn’t respond well to prolonged mutual gaze”). (Bailenson et al. 2005, pp. 435-436)

While this method can bring about change in non-verbal behaviors as represented in the CVE and thus achieve the same strategic goals by the same means in the second (psychological) step, it does not do so in the characteristic TSI way: it doesn’t decouple the representation from the behavior; instead it changes the behavior itself in the desired way. I think our understanding of the core of TSI is improved by excluding this kind of active mediation (even that presented by Bailenson et al.) and considering it instead a proper part of the superset – actively mediated communication. With this broadened scope we can take advantage of the wider range of strategies, taxonomies, and examples available from the study of persuasive technology.

TSI ideas outside CVEs

TSI is established as applying to CVEs. Standard TSI examples take place in CVEs and the feasibility of TSI is discussed with regard to CVEs. This focus is also manifest in the fact that it is behaviors, identity cues, and sensing that are normally available that are the starting point for transformation. Some of the more radical transformations of sensing and identity are nonetheless explained with reference to real-world manifestation: for example, helpers walk like ghosts amongst those you are persuading, reporting back on what they learn.

But I think this latter focus is just an artifact of the fact that, in a CVE, all the strategic transformations have to be manifest as representations of face-to-face encounters. As evidence for the anticipation of the generalization of TSI ideas beyond CVEs, we see that Bailenson et al. (2005, p. 428) introduce TSI with examples from the kind of outright blocking of any representation of particular non-verbal behaviors in telephone calls. Of course, this is not the kind of dynamic transformation characteristic of TSI, but this highlights how TSI ideas make sense outside of CVEs as well. To make it more clear what I mean by this, I present three examples: transformation of a shared drawing, coaching and augmentation in face-to-face conversation, and aggregation and synthesis in an SNS-based event application, like Facebook Events.

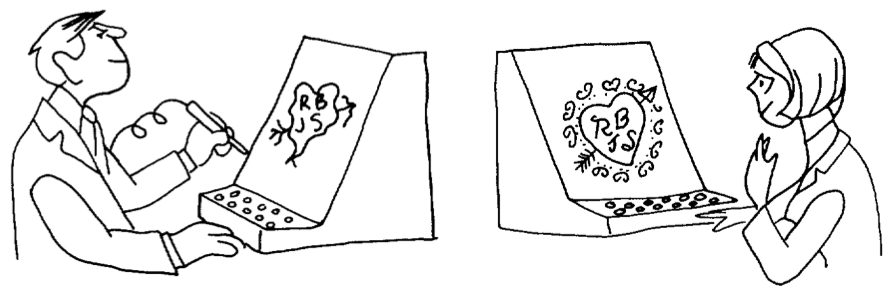

This more general notion of actively mediated communication is present in the literature as early as 1968 with the work of Licklider & Taylor (1968). In one interesting example, which is also a great example of 1960s gender roles, a man is draws an arrow-pierced heart with his initials and the initials of a romantic interest or partner, but when this heart is shared with her (perhaps in real time as he draws it), it is rendered as a beautiful heart with little resemblance to his original, poor sketch. The figure illustrating the example is captioned, “A communication system should make a positive contribution to the discovery and arousal of interests” (Licklider & Taylor 1968, p. 26). This example clearly exemplifies the idea of TSI – decoupling the original behavior from its representation in a strategic way that requires an intelligent process (or human-in-the-loop) making the transformation responsive to the specific circumstances and goals.

Licklider & Taylor also consider examples in which computers take an active role in a face-to-face presentation by adding a shared, persuasive simulation (cf. Fogg 2002 on computers in the functional role of interactive media such as games and simulations). But a clearer example, that also bears more resemblance to characteristic TSI examples, is conversation and interaction coaching via a wireless headset that can determine how much each participant is speaking, for how long, and how often they interrupt each other (Kass 2007). One could even imagine a case with greater similarity to the TSI example considered in the previous case: a device whispers in your ear the known preferences of the person you are talking to face-to-face (e.g., that he doesn’t respond well to prolonged mutual gaze).

Finally, I want to share an example that is a bit farther afield from TSI exemplars, but highlights how ubiquitous this general category is becoming. Facebook includes a social event planning application with which users can create and comment on events, state their plans to attend, and share personal media and information before and after it occurs. Facebook presents relevant information about one’s network in a single “News Feed”. Event related items can appear in this feed, and they feature active mediation: a user can see an item stating that “Jeff, Angela, Rich, and 6 other friends are attending X. It is at 9pm tonight” – but none of these people or the event creator, ever wrote this text. It has been generated strategically: it is encouraging considering coming to the event and it is designed to maximize the user’s sense of relevance of their News Feed. The original content, peripheral behavior, and form of their communications have been aggregated and synthesized into a new communication that better suits the situation than the original.

Source orientation in actively mediated communication

Bailenson et al. (2005) considers the consequences of TSI for trust in CVEs and how possible TSI detection is. I’ve suggested that we can see TSI-like phenomena, both actual and possible, outside of CVEs and outside of a narrow version of TSI in which directly changing (programmatically) the represented behavior without changing the actual behavior is required. Many of the same consequences for trust may apply.

But even when the active mediation is to some degree explicit – participants are aware that some active mediation is going on, though perhaps not exactly what – interesting questions about source orientation still apply. There is substantial evidence that people orient to the proximal rather than distal source in use of computers and other media (Sundar & Nass 2000, Nass & Moon 2000), but this work has been limited to relatively simple situations, rather than the complex multi-sourced, actively mediated communications under discussion. I think we should expect that proximality will not consistently predict degree of source orientation (impact of source characteristics) in these circumstances: the most proximal source may be a dumb terminal/pipe (cf. the poor evidence for proximal source orientation in the case of televisions, Reeves & Nass 1996), or the most proximal source may be an avatar, the second most proximal might be a cyranoid/ractor or a computer process, while the more distant is the person whose visual likeness is similar to that of the avatar; and in these cases one would expect the source orientation to not be the most proximal, but to be the sources that are more phenomenologically present and more available to mind.

This seems like a promising direction for research to me. Most generally, it is part of the study of source orientation in more complex configurations – with multiple devices, multiple sources, and multiple brands and identities. Consider a basic three condition experiment in which participants interact with another person and are either told (1) nothing about any active mediation, (2) there is a computer actively mediating the communications of the other person, (3) there is a human (or perhaps multiple humans) actively mediating the communications of the other person. I am not sure this is the best design, but I think it hints in the direction of the following questions:

- When and how do people apply familiar social cognition strategies (e.g., folk psychology of propositional attitudes) to understanding, explaining, and predicting the behavior of a collection of people (e.g., multiple cyranoids, or workers in a task completion market like Amazon Mechanical Turk)?

- What differences are there in social responses, source orientation, and trust between active mediation that is (ostensibly) carried out by (1) a single human, (2) multiple humans each doing very small pieces, (3) a computer?

References

Eckles, D., Ballagas, R., Takayama, L. (unpublished manuscript). The Design Space of Computer-Mediated Communication: Dimensional Analysis and Actively Mediated Communication.

Fogg, B.J. (2002). Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do. Morgan Kaufmann.

Kass, A. (2007). Transforming the Mobile Phone into a Personal Performance Coach. Mobile Persuasion: 20 Perspectives on the Future of Influence, ed. B.J. Fogg & D. Eckles, Stanford Captology Media.

Licklider, J.C.R., & Taylor, R.W. (1968). The Computer as a Communication Device. Science and Technology, April 1968. Page numbers from version reprinted at http://gatekeeper.dec.com/pub/DEC/SRC/research-reports/abstracts/src-rr-061.html.

Nass, C., and Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and Mindlessness: Social Responses to Computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81-103.

Oinas-Kukkonen, H., & Harjumaa, M. (2008). A Systematic Framework for Designing and Evaluating Persuasive Systems. In Proceedings of Persuasive Technology: Third International Conference, Springer, pp. 164-176.

Sundar, S. S., & Nass, C. (2000). Source Orientation in Human-Computer Interaction Programmer, Networker, or Independent Social Actor? Communication Research, 27(6).

- This idea is expanded upon in Eckles, Ballagas, and Takayama (ms.), to be presented at the workshop on Socially Mediating Technologies at CHI 2009. This working paper will be available online soon. [↩]

Producing, consuming, annotating (Social Mobile Media Workshop, Stanford University)

Today I’m attending the Social Mobile Media Workshop at Stanford University. It’s organized by researchers from Stanford’s HStar, Tampere University of Technology, and the Naval Postgraduate School. What follows is some still jagged thoughts that were prompted by the presentation this morning, rather than a straightforward account of the presentations.1

A big theme of the workshop this morning has been transitions among production and consumption — and the critical role of annotations and context-awareness in enabling many of the user experiences discussed. In many ways, this workshop took me back to thinking about mobile media sharing, which was at the center of a good deal of my previous work. At Yahoo! Research Berkeley we were informed by Marc Davis’s vision of enabling “the billions of daily media consumers to become daily media producers.” With ZoneTag we used context-awareness, sociality, and simplicity to influence people to create, annotate, and share photos from their mobile phones (Ahern et al. 2006, 2007).

Enabling and encouraging these behaviors (for all media types) remains a major goal for designers of participatory media; and this was explicit at several points throughout the workshop (e.g., in Teppo Raisanen’s broad presentation on persuasive technology). This morning there was discussion about the technical requirements for consuming, capturing, and sending media. Cases that traditionally seem to strictly structure and separate production and consumption may be (1) in need of revision and increased flexibility or (2) actually already involve production and consumption together through existing tools. Media production to be part of a two-way communication, it must be consumed, whether by peers or the traditional producers.

As an example of the first case, Sarah Lewis (Stanford) highlighted the importance of making distance learning experiences reciprocal, rather than enforcing an asymmetry in what media types can be shared by different participants. In a past distance learning situation focused on the African ecosystem, it was frustrating that video was only shared from the participants at Stanford to participants at African colleges — leaving the latter to respond only via text. A prototype system, Mobltz, she and her colleagues have built is designed to change this, supporting the creation of channels of media from multiple people (which also reminded me of Kyte.tv).

As an example of the second case, Timo Koskinenen (Nokia) presented a trial of mobile media capture tools for professional journalists. In this case the work flow of what is, in the end, a media production practice, involves also consumption in the form of review of one’s own materials and other journalists, as they edit, consider what new media to capture.

Throughout the sessions themselves and conversations with participants during breaks and lunch, having good annotations continued to come up as a requirement for many of the services discussed. While I think our ZoneTag work (and the free suggested tags Web service API it provides) made a good contribution in this area, as has a wide array of other work (e.g., von Ahn & Dabbish 2004, licensed in Google Image Labeler), there is still a lot of progress to make, especially in bringing this work to market and making it something that further services can build on.

References

Ahern, S., Davis, M., Eckles, D., King, S., Naaman, M., Nair, R., et al. (2006). ZoneTag: Designing Context-Aware Mobile Media Capture. In Adjunct Proc. Ubicomp (pp. 357-366).

Ahern, S., Eckles, D., Good, N. S., King, S., Naaman, M., & Nair, R. (2007). Over-exposed?: privacy patterns and considerations in online and mobile photo sharing. In Proc. CHI 2007 (pp. 357-366). ACM Press.

Ahn, L. V., & Dabbish, L. (2004). Labeling images with a computer game. In Proc. CHI 2004 (pp. 319-326).

- Blogging something at this level of roughness is still new for me… [↩]